No one goes into the legal profession thinking it is going to be easy. Long working hours are fairly standard, work is often completed to tight external deadlines, and 24/7 availability to clients is widely understood to be a norm, particularly in commercial and international practice.

But too often, the demands of law can create an unhealthy workplace environment. In 2021, the stress of high workloads, low job control, and risks of secondary trauma led SafeWork NSW to categorise legal work as "high risk" for fatigue hazards - putting it alongside night shift work, emergency services, and fly-in, fly-out roles.

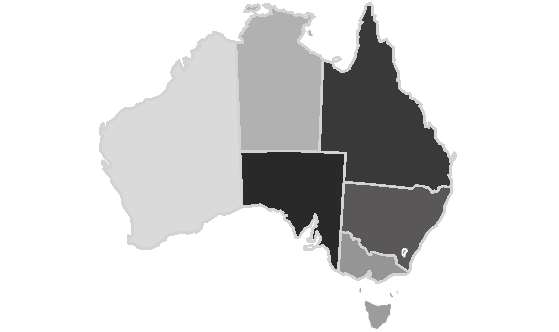

To investigate this problem, we surveyed about 1,900 lawyers across Victoria, New South Wales and Western Australia in March and April last year.

We asked them about their workplace culture and its impact on wellbeing, about their levels of psychological distress, and whether they had experienced disrespectful behaviours at work.

We also asked whether they intended to leave either their employer or the legal profession in the near future.

Their answers allowed us to identify the type of workplace culture that is harmful to lawyers' wellbeing. Here's why fixing this problem matters to us all.

Among the professionals we surveyed, about half found themselves in a workplace culture with negative effects on wellbeing.

A third of this group said their workplaces were characterised by poor working relationships, self-interest and pressure to cut corners or bend rules.

These poorer workplace cultures involved higher levels of psychological distress and more disrespectful behaviours from superiors and coworkers.

They were also characterised by a lack of effective wellbeing supports such as mental health leave arrangements or workload allocation practices.

Long working hours were common. More than half of participants (53%) said they worked more than 40 hours per week and 11% said they put in more than 60 hours.

About a third of the lawyers we surveyed wanted to quit their firm, while 10% planned to leave the profession, within a year.

Society can't afford to ignore this problem. Lawyer wellbeing can directly affect the quality of legal services and may even lead to disciplinary action against individual lawyers. All of this can undermine public trust and confidence in the justice system.

We invited participants to explain why they intended to leave the profession. Their answers are telling.

One mid-career lawyer at a large firm said:

I am in my 11th year of practice working as a Senior Associate at a top-tier firm. To put it bluntly, the work rate at which I am currently operating, which is required to meet the billable targets and budgets set for us, cannot be sustained for my whole working life - it's too much.

A small-firm junior lawyer talked of the workload issues described by many:

The pay is not worth the stress. I can't sleep because I'm constantly worried about deadlines or making mistakes, and I got paid more when I was a bartender. I love the work, but it's a very tough slog and damaging my own wellbeing - for what?

Our data showed junior lawyers take a lot of the pressure, reflected in higher-than-average levels of psychological distress. Equally concerning was the extent to which senior lawyers with practice management responsibilities also reported above average distress.

Our research also showed the challenges extended beyond private practice and into government, legal aid and corporate "in-house" settings.

As one mid-career legal aid lawyer put it:

Lack of debriefing and supports, lack of formal mentoring and supervision, mental health toll, high workload and poor workplace culture, lack of training and supports to deal with clients in crisis, [mean it's] not [a] family-friendly profession.

There was also good news. Three themes stood out in the responses from the 48% who told us they worked in positive workplace cultures. This suggests where support should be targeted.

For nearly two thirds of our sample, having good colleagues was the most important wellbeing support. As one mid-career lawyer put it:

Informal support such as debriefing with colleagues has been most beneficial for me.

Good flexible working and (mental health) leave arrangements came across as the most important practical support employers could provide.

Good workload allocation practices - and a willingness from managers to "reach out to discuss work-life balance" - make a real difference to peoples' experience.

The legal profession and its regulators have been engaging with the wellbeing problem for a while now. Our findings suggest there is still more to be done.

For the profession as a whole we felt that there was still a need to develop greater understanding of the specific wellbeing needs of both junior lawyers and those managing them, as these are the two groups experiencing the most distress.

Legal regulatory bodies should work to better understand how economic drivers of legal practice, such as high workloads and billing expectations, can have negative consequences for wellbeing, and whether any regulatory levers could lessen these impacts.

The authors would like to acknowledge the significant contribution of Stephen Tang, clinical psychologist, in undertaking data analysis and coauthoring the original report.